Dialogic Intelligence

What It Is, and Why AI Makes It Urgent

Intelligence isn’t about getting the right answer on a test someone else has devised - it’s about making complex decisions when no one can tell you what is best and asking the kind of questions that reveal new things.

The challenge

Teachers I talk to about generative AI often express the concern that it will dumb students down, encouraging them to outsource their critical thinking and stop learning for themselves. There are now some published studies providing solid evidence justifying this anxiety.

Despite the evidence I always find this concern a bit surprising because I use AI all the time in ways that seems to me to expand my knowledge and my understanding. Whenever I get an inkling of a new idea I run it by my AI companion for comment. When it tells me, as it usually does ‘what a profound and insightful idea, Rupert’, I push back asking: imagine you were someone who disagreed with this idea, what are the main criticisms you would make? What are the implications? Has anyone else said something similar? Working constantly with AI in this way has expanded my knowledge and understanding.

So here’s the puzzle: if AI can support such expansive thinking for me and many others, why is it so often experienced in schools and universities as a threat to independent thought? The answer, I suspect, lies not in the technology but in the pedagogy. If we plug generative AI into an education system that prizes right answers and neatly packaged essays then of course students will use AI to game the system. At Cambridge we imagine we are assessing the original thinking of students with essay titles requiring a ‘personal synthesis’ of an area often grading them higher for ‘critical thinking’ and ‘signs of original thought’. The fact that AI seems remarkably good at generating these sorts of essays should really make us question the validity of our assessments. If AI can ace all the assessments then it is not surprising that students who are trained to want higher marks will use the AI and as a result get dumbed down because they are not doing the work for themselves. The problem here is not with the technology but with our education system. To respond we need to rethink not only our assessments but also what we are teaching and why we are teaching it.

Some good examples

Earlier this year I visited an old colleague from the UK Open University, Simon Buckingham Shum, now at the University of Technology (UTS) Sydney. Simon has been leading an initiative to integrate AI across the curriculum. The strategy of UTS is not to ban AI but to use it as a ‘powerful thinking partner’. To help with this he has developed several customised chatbots including ‘QReframer’, which brings out the assumptions behind every question and encourages you to engage in discussing them further. I had doubts about this so I tried it out the next week in workshops with a few hundred teachers in Adelaide and they all found it very useful. If you ask it how to use AI to help with assessment for example, it will challenge you to think carefully about what you are assessing and why and if this is compatible with AI.

Simon is not alone. Many educators are developing excellent practice with AI. Nick Potkalitsky, working with students in the US, encourages learners to approach AI not as an answer dispenser but as a co-inquirer — a way to open what he calls a dialogic space for iterative thinking. His method involves guiding students through a sequence of steps: they begin by surfacing their own implicit assumptions, then use AI to challenge or complicate those premises, before co-developing new lines of inquiry in response. One student described the process as “thinking in layers,” where AI isn’t offering solutions so much as provoking further and deeper questions. Using AI in this way means that students are not just solving problems but reshaping the way they understand them.

Rethinking “intelligence”

The term intelligence derives from the Latin intelligere, a compound of inter- (“between”) and legere (“to gather,” “to read”), suggesting the capacity to “read between” or discern patterns across contexts. This Latin root legere itself stems from the Proto-Indo-European root leg- or leǵ- (“to collect,” “to choose,” “to speak”), which also gives rise to the ancient Greek logos (λόγος). While logos is often translated as “word,” “reason,” or “discourse,” its deeper etymological connection to leg- implies a more fundamental act of gathering meaning—perceiving pattern, coherence, and relational order.

Intelligence, understood as “reading between” (inter-legere), and logos understood with Socrates as the living word—a word always in relationship with others and the world—point us to what education should be. Yet this is not what we have been teaching or valuing. Our systems reward the capacity to deliver the “right” answer as quickly and independently as possible. We celebrate as ‘high IQ’ those who can swiftly solve problems already solved by others. We appear to have fallen into the very trap Socrates warned against: mistaking the image of knowledge for the real thing, and training minds not for insight, but for repetition. True learning, Socrates claimed —the kind that brings joy and also, he writes, a kind of immortality—emerges only through participation in logos understood as living dialogue.

Dialogic education

Some people say that dialogue is all about empathy and since AI cannot have real empathy then it is not really dialogic. But that is not what we have seen in research on learners thinking together. Dialogue is not simply about being nice or about sharing feelings. It’s more about being challenged, and allowing that challenge to open a ‘dialogic space’ in which new meaning can emerge. Dialogue, in this sense, is an answer to the question: how is it possible to learn something new?

Given the challenge to existing education offered by the advent of Generative AI it is lucky that over the past 30 years we have developed dialogic education as a way to cultivate just the kind of intelligence required for thinking together with AI: dialogic intelligence

Dialogic Intelligence

The word dialogic is a neat technical term that implies meaning is not self-contained. Words don’t only mean what the dictionary says—they mean in context, in relation to what they’re responding to and what they hope to elicit in the future. Dialogic is the living word Socrates referred to. Dialogic meaning only emerges when at least two perspectives interact or clash. This is in contrast to monologic, which implies one right answer, one authoritative view.

True intelligence isn’t just about algorithmic logic or having the right answer—it’s the capacity to navigate complexity, to shift perspective, and to make sense when there is no single, clear path.

Dialogic intelligence resonates with the competencies in the 21st Century Skills Framework—creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration (the so-called 4Cs). But rather than treating these as individual traits, we understand them here as relational capacities: the ability to participate in shared thinking—thinking together with others, and increasingly, with AI agents.

In the past, we’ve evaluated the impact of dialogic education using non-verbal reasoning tests drawn from IQ assessments and found strong results. We’ve also demonstrated its value on standardised learning measures. But all these tests are, by design, monologic—they’re based on the idea of a single correct answer.

At DEFI (DEFICambridge.org), we’re working on several projects to promote dialogic intelligence. One uses AI to train managers in handling difficult conversations. Another is developing an AI moderator bot to support more intelligent online discussions. Assessing these projects require us to evaluate progress in dialogic intelligence.

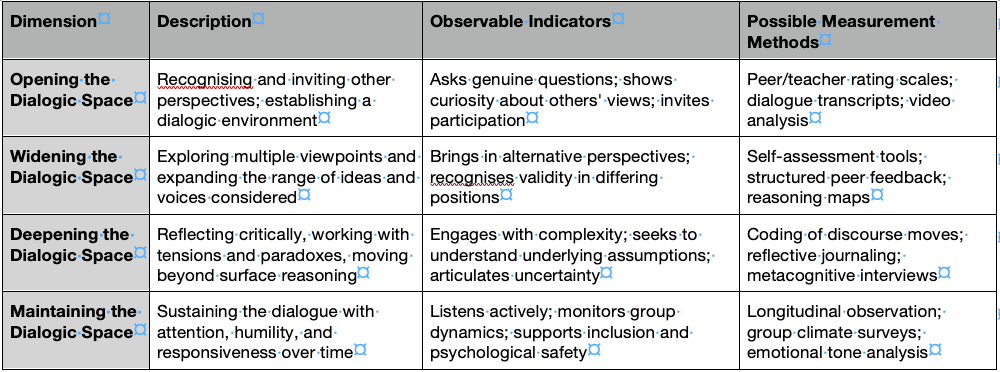

My own understanding is that dialogic education works by expanding dialogic space. That involves opening a space, widening it by bringing in a range of voices, and deepening it by questioning framing assumptions. But it also requires moves to maintain the space—preventing it from collapsing either into monologism or into chaotic noise.

One possible way to assess the development of dialogic intelligence might look like this:

Last word

AI can now outperform most students on standard educational assessments. Relying on AI within this system risks preventing students from learning for themselves. But teaching students to do what AI already does better seems like a waste of time anyway.

The alternative is to reorient education to focus on thinking —thinking together with other people, and with AI tools. This is the goal of dialogic education.

The fruit of dialogic education is dialogic intelligence: not the ability to work alone to quickly answer questions set by others, but the capacity to participate meaningfully in shared thinking, driven by real questions that matter.

Hello Rupert,

I greatly appreciate your work on dialogic education. I am the creator of a conversational process known as the Knowledge Café, which I have been running around the world for the past 20 years, both face-to-face and online. Its design has much in common with your thinking.

I am particularly interested in the use of generative AI as a thinking partner and have written about how chatbots can be used to aid critical thinking. If you are interested, you will find a chapter on this in my online blook on Conversational Leadership.

Best wishes, David

https://conversational-leadership.net/chatbots-to-aid-critical-thinking/?pr=ss

Your description of dialogue space reminded me of creative problem solving