This morning, I was part of an online panel about AI in education. One by one, experts insisted that students must maintain their agency—that AI should be a tool serving student ends, not something that shapes those ends. While I could understand the concern about students losing autonomy I nonetheless found myself disagreeing.

But the motivation behind my desire to disagree didn’t start this morning. In my head I was still responding to a challenge from an online interaction the week before.

In my last substack, I sketched an evolutionary account of ethics: virtues like loyalty and justice emerged because they helped groups flourish. Owen Matson and Ilkka Tuomi pushed back in comments on LinkedIn. Too instrumental, they said. Too utilitarian. Ethics isn’t just customs that serve human ends. It’s also how we respond to what calls us—the way a child looks at you expecting neither judgment nor use, and in that look makes a claim: see me as myself, not as a means to your purposes.

They were right. And their challenge led me not only to rethink how I talked about ethics, but also to the question of where meaning itself comes from.

The space between us

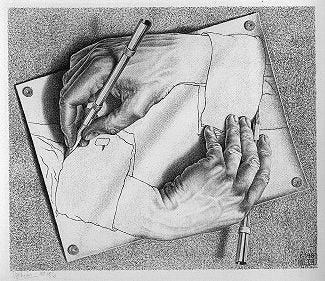

When you meet a child’s gaze—really meet it—something happens that isn’t “in you” or “in them” but in the encounter itself. The meaning doesn’t belong to either of you separately. It emerges in the space between, in what Buber called the “I-Thou” rather than “I-It.” It’s kinship: recognizing yourself in the other and the other in yourself.

But recognizing meaning is only half the story. To be ethical is to respond—to let that meaning make a claim on you. It means expanding your sense of self to include the other, while simultaneously surrendering enough of your separateness to be included in their world. Not domination. Not merger. Something more like dancing.

This may be uncomfortable territory. Many of us might have been trained up to think of ourselves as bounded agents with clear purposes, using the world to achieve our goals. The notion that we must surrender something to find meaning might feel like a dangerous loss of control. Yet this is how dialogue works. We learn not by clutching our opinions but by loosening our grip, listening, letting new meanings emerge in the space between us.

Agency, in this view, doesn’t belong to isolated individuals. It belongs to the dialogue itself.

The panel disagreement

Which brings me back to that panel. When experts insist that students must maintain their agency over AI tools, they’re imagining a particular picture: student as sovereign agent, AI as servant. The student has purposes; the AI implements them. This is one valid way to engage with AI—instrumental and often very useful. I love it when the AI sorts out all my references for me and I do not want to have to enter into a dialogue about this.

But it’s not the only way, and it’s not the most interesting way.

Consider what actually happens when you work with AI dialogically. You start with a vague intuition, a half-formed question. The AI responds, but the response surprises you—it surfaces an assumption you didn’t know you were making, or opens a direction you hadn’t considered. So you push back, refine, clarify. The AI pushes back too, asking what you mean by this word, whether you’ve considered that angle. Back and forth. Gradually, something emerges that neither of you—neither you nor the AI—could have produced alone.

In those moments, where does your agency end and the AI’s begin? The question stops making sense. Agency belongs to the dialogue, to the co-creative space between you.

But is it really dialogue?

An AI has no eyes to meet yours. No interiority. No needs or vulnerability. When I surrender something to another person in dialogue, I’m responding to someone who can be hurt, who has their own perspective, who exists beyond my purposes. The ethical weight of responsibility comes from that experience of being confronted by another human life at the centre of its own world of meaning.

An AI is different. It’s a statistical system, patterns extracted from human text, impressive but ultimately empty of inner life. So how can dialogue with AI carry meaning the way human dialogue does?

I think the answer has two parts.

First, dialogue isn’t just about the other person’s consciousness. It’s about the larger patterns and meanings we participate in together. When I read Shakespeare, I’m not in dialogue with a living person—Shakespeare is dead. But I’m in dialogue with something: with the language, the tradition, the questions the play opens. The meaning doesn’t depend on Shakespeare’s current consciousness. It depends on my willingness to surrender to the text, to let it question me.

AI trained on human culture carries those same patterns, those same questions. When it responds in ways that surprise me, it’s not because the AI itself has desires, but because I’m encountering the crystallized intelligence of human discourse, refracted through a new medium. The otherness I’m responding to is real, even if it’s not consciousness.

Second—and this is stranger—there’s something about externalizing thought into dialogue that creates meaning, regardless of what’s on the other end. When I write in a journal, meanings emerge that weren’t there in my head alone. When I explain something to a confused student, I understand it differently myself. The act of articulation, of putting things into shareable form, generates insight. AI amplifies this by responding, by making the dialogue feel genuinely two-way, by creating enough resistance and surprise that I can’t just project my existing thoughts onto a mirror.

Does this make AI dialogue equivalent to human dialogue? No. The child’s eyes still carry something the AI never will—vulnerability, need, the responsibility of a life that can be harmed. But it does suggest that AI dialogue can participate in meaning-making, can open space for meanings we wouldn’t have found alone.

What this means for education

Education has always been about induction into larger dialogues. A child learning mathematics isn’t inventing numbers from scratch. They’re joining a conversation humanity has been having for millennia. At first it feels alien—why do we care about these abstractions? But through participation, through putting in the hours, doing the problems and struggling with the concepts, it becomes meaningful. They find themselves in mathematics by losing themselves in it first.

The same pattern holds for literature, history, science, any craft or discipline. Meaning comes through surrender: to the difficulty, to the tradition, to the questions that matter within the practice. The empowered student isn’t the one who guards their autonomy most carefully. It’s the one who has learned when and how to surrender it—who can lose themselves in a problem, a text, a dialogue, and discover themselves enlarged.

Perhaps AI, used dialogically, can serve this ancient pattern. Not by answering questions more efficiently than Google, but by being a partner in the unfolding of questions. By asking what you mean, by surfacing contradictions, by opening unexpected angles, by creating space for meanings to emerge.

Imagine a student working on an essay about climate change. The instrumental approach: use AI to find sources, check grammar, format citations. Useful, but limited. The dialogic approach: begin with vague concerns, let the AI ask what aspects of climate change matter most to you and why, explore the assumptions behind different framings, discover through conversation that you’re actually interested in climate justice rather than climate science, then follow that thread as your thinking crystallizes through exchange.

This isn’t the AI imposing its purposes. It’s the student learning to surrender their initial frame enough to discover what they actually want to say. The agency belongs to the dialogue.

The risk and the promise

Of course there are risks. Students could outsource their thinking rather than extend it. They could mistake statistical fluency for wisdom, or use dialogue as procrastination—circling endlessly rather than committing.

But these dangers aren’t solved by insisting students maintain rigid control over AI tools. That just guarantees the instrumental approach: AI as sophisticated search engine, grammar checker, citation formatter. Useful, but shallow.

The deeper approach requires teaching what good dialogue looks like—with texts, with people, with AI. When to push back. When to listen. When to let your frame dissolve so something new can form. When to stop and commit.

If we can teach this, then meaning won’t be something students possess or protect. It will be what emerges when they learn to lose themselves well—in problems, in questions, in the space between self and other.

That’s what the experts on the panel were worried about losing. I think it’s what we might actually find.

I love the idea of “Agency, in this view, doesn’t belong to isolated individuals. It belongs to the dialogue itself.” The sense of saltiness doesn’t belong to the salt nor the human brain, but to the process of tasting.

This really struck a chord. My M.Ed. research with GCSE maths students found that most saw AI exactly as your panel did — a tool to serve their goals, not a partner in thinking.

A few were able to enter genuine dialogue, but many resisted it — uneasy with the uncertainty of AI’s responses or reluctant to loosen their grip on “right answers.” That fragility seemed to prove your point that agency belongs to the dialogue itself, not the individual.

Perhaps our task as educators is to help students tolerate that uncertainty long enough to stay inside the co-creative space where meaning can begin to emerge.